Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT) is a rapid heart rate. It occurs when too many signals (electrical impulses) are sent from the upper heart (atria) to the lower heart (ventricles).

Causes

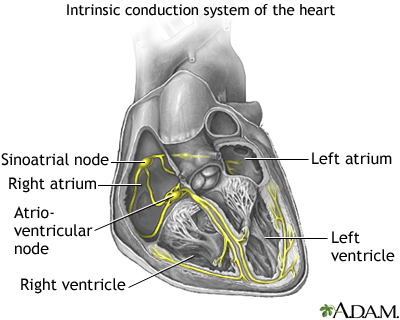

The human heart gives off electrical impulses, or signals, which tell it to beat. Normally, these signals begin in an area of the upper right chamber called the sinoatrial node (sinus node or SA node). This node is considered the heart's "natural pacemaker." It helps control the heartbeat. When the heart detects a signal, it contracts (or beats).

The normal heart rate in adults is 60 to 100 beats per minute. The normal heart rate is faster in children.

In MAT, many locations in the atria fire signals at the same time. Too many signals lead to a rapid heart rate. It most often ranges from 100 to 130 beats per minute or more in adults. The rapid heart rate may cause the heart to work too hard and not move blood efficiently. If the heartbeat is very fast, there is less time for the heart chamber to fill with blood between beats. Therefore, not enough blood is pumped to the brain and the rest of the body with each contraction.

MAT is most common in people age 50 and over. It is often seen in people with conditions that lower the amount of oxygen in the blood. These conditions include:

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Heart failure (also called congestive heart failure)

- Lung cancer

- Lung failure

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary embolism

You may be at higher risk for MAT if you have:

- Coronary heart disease

- Diabetes

- Had surgery within the last 6 weeks

- Overdosed on the drug theophylline

- Sepsis

When the heart rate is less than 100 beats per minute, the arrhythmia is called "wandering atrial pacemaker."

Symptoms

Some people may have no symptoms. When symptoms occur, they can include:

- Chest tightness

- Fainting

- Lightheadedness

- Sensation of feeling the heart is beating irregularly or too fast (palpitations)

- Shortness of breath

- Weight loss and failure to thrive in infants

Other symptoms that can occur with this disease:

Exams and Tests

A physical exam shows a fast irregular heartbeat of over 100 beats per minute. Blood pressure is normal or low. There may be signs of poor circulation.

Tests to diagnose MAT include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG)

- Electrophysiologic study (EPS)

Heart monitors may be used to record the rapid heartbeat. These include:

- 24-hour Holter monitor

- Portable, long-term loop recorders that allow you to start recording if symptoms occur

If you are in the hospital, your heart rhythm will be monitored 24 hours a day, at least at first.

Treatment

If you have a condition that can lead to MAT, that condition should be treated first.

Treatment for MAT includes:

- Improving blood oxygen levels

- Giving magnesium or potassium through a vein

- Stopping medicines, such as theophylline, which can increase heart rate

- Taking medicines to slow the heart rate (if the heart rate is too fast), such as calcium channel blockers (verapamil, diltiazem) or beta-blockers

Outlook (Prognosis)

MAT can be controlled if the condition that causes the rapid heartbeat is treated and controlled.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Cardiomyopathy

- Heart failure

- Reduced pumping action of the heart

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your health care provider if:

- You have a rapid or irregular heartbeat with other MAT symptoms

- You have MAT and your symptoms get worse, do not improve with treatment, or you develop new symptoms

Prevention

To reduce the risk for developing MAT, treat the disorders that cause it right away.

Alternative Names

Chaotic atrial tachycardia

References

Kalman JM, Sanders P. Supraventricular tachycardias. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 65.

Zimetbaum P, Goldman L. Supraventricular ectopy and tachyarrhythmias. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 52.

Review Date 5/27/2024

Updated by: Michael A. Chen, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington Medical School, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.