Ventricular assist devices (VADs) help your heart pump blood from one of the main pumping chambers to the rest of your body or to the other side of the heart. These pumps are implanted in your body. In most cases, they are connected to machinery outside your body.

Description

A ventricular assist device has 3 parts:

- A pump. The pump weighs 1 to 2 pounds (0.5 to 1 kilogram). It is placed inside or outside of your belly.

- An electronic controller. The controller is a small computer that controls how the pump works.

- Batteries or another power source. The batteries are carried outside your body. They are connected to the pump with a cable that goes into your belly.

If you are having an implanted VAD placed, you will need general anesthesia. This will make you sleep and be pain-free during the procedure.

During surgery:

- The heart surgeon opens the middle of your chest with a surgical cut and then separates your breastbone. This allows access to your heart.

- Depending on the pump used, the surgeon will make space for the pump under your skin and tissue in the upper part of your belly wall.

- The surgeon will then place the pump in this space.

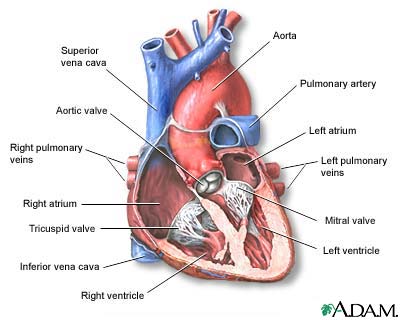

A tube will connect the pump to your heart. Another tube will connect the pump to your aorta or one of your other major arteries. Another tube will be passed through your skin to connect the pump to the controller and batteries.

The VAD will take blood from your ventricle (one of the main pumping chambers of the heart) through the tube that leads to the pump. Then the device will pump the blood back out to one of your arteries and through your body.

Surgery most often lasts 4 to 6 hours.

There are other types of VADs (called percutaneous ventricular assist devices) which can be placed with less invasive techniques to help the left or right ventricle. However, these typically cannot provide as much flow (support) as the surgically implanted ones.

Why the Procedure is Performed

You may need a VAD if you have severe heart failure that cannot be controlled with medicine, pacing devices, or other treatments. You may get this device while you are on a waiting list for a heart transplant. Some people who get a VAD are very ill and may already be on a heart-lung support machine.

Not everyone with severe heart failure is a good candidate for this procedure.

Risks

Risks for this surgery are:

- Blood clots in the legs that may travel to the lungs

- Blood clots that form in the device and can travel to other parts of the body

- Breathing problems

- Heart attack or stroke

- Allergic reactions to the anesthesia medicines used during surgery

- Infections

- Bleeding

- Death

Before the Procedure

Many people will already be in the hospital for treatment of their heart failure.

After the Procedure

Most people who are put on a VAD spend from a few to several days in the intensive care unit (ICU) after surgery. You may stay in the hospital for a week or longer after you have had the pump placed. During this time you will learn how to care for the pump.

Less invasive VADs are not designed for ambulatory patients and those patients need to stay in the ICU for the duration of their use. They are sometimes used as a bridge to a surgical VAD or heart recovery.

Outlook (Prognosis)

A VAD may help people who have heart failure live longer. It may also help improve patients' quality of life.

Alternative Names

VAD; RVAD; LVAD; BVAD; Right ventricular assist device; Left ventricular assist device; Biventricular assist device; Heart pump; Left ventricular assist system; LVAS; Implantable ventricular assist device; Heart failure - VAD; Cardiomyopathy - VAD

References

Aaronson KD, Pagan FD. Mechanical circulatory support. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 59.

Chieffo A, Dudek D, Hassager C, et al. Joint EAPCI/ACVC expert consensus document on percutaneous ventricular assist devices. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2021;10(5):570-583. PMID: 34057173 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34057173/.

Cook JL, Colvin M; American Heart Association Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, et al. Recommendations for the use of mechanical circulatory support: ambulatory and community patient care: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(25):e1145-e1158. PMID: 28559233 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28559233/.

Holman WL, Kociol RD, Pinney S. Postoperative VAD management: operating room to discharge and beyond: surgical and medical considerations. In: Kirklin JK, Rogers JG, eds. Mechanical Circulatory Support: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 12.

Rihal CS, Naidu SS, Givetz MM, et al. 2015 SCAI/ACC/HFSA/STS clinical expert consensus statement on the use of percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices in cardiovascular care: endorsed by the American Heart Association, the Cardiological Society of India, and Sociedad Latino Americana de CardiologiaIntervencion; affirmation of value by the Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology-Association Canadienne de Cardiologied'intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):e7-e26. PMID: 25861963 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25861963/.

Review Date 5/27/2024

Updated by: Michael A. Chen, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington Medical School, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.