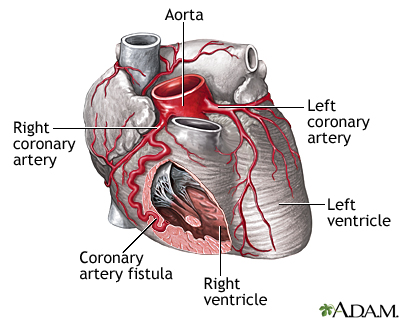

Coronary artery fistula is an abnormal connection between one of the coronary arteries and a heart chamber or another blood vessel. The coronary arteries are blood vessels that bring oxygen-rich blood to the heart.

Fistula means abnormal connection.

Causes

A coronary artery fistula is often congenital, meaning that it is present at birth. It generally occurs when one of the coronary arteries fails to form properly. This most often takes place when the baby is developing in the womb. The coronary artery abnormally attaches to one of the chambers of the heart (the atrium or ventricle) or another blood vessel (for example, the pulmonary artery).

A coronary artery fistula can also develop after birth. It may be caused by:

- An infection that weakens the wall of the coronary artery and the heart

- Certain types of heart surgery

- Injury to the heart from an accident or surgery

Coronary artery fistula is a rare condition. Infants who are born with it sometimes also have other heart defects. These may include:

Symptoms

Infants with this condition often do not have any symptoms.

If symptoms do occur, they can include:

- Heart murmur

- Chest discomfort or pain

- Easy fatigue

- Failure to thrive

- Fast or irregular heartbeat (palpitations)

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea)

Exams and Tests

In most cases, this condition is not diagnosed until later in life. It is most often diagnosed during tests for other heart diseases. However, the health care provider may hear a heart murmur that will lead to the diagnosis with further testing.

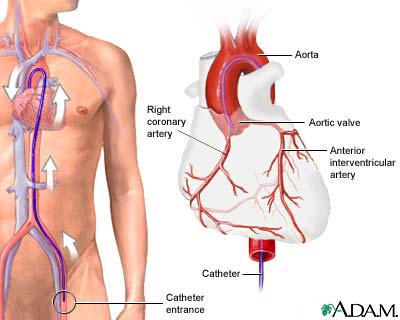

The main test to determine the size of the fistula is a coronary angiography. This is a special x-ray test of the heart using dye to see how and where blood is flowing. It is often done along with cardiac catheterization, which involves passing a thin, flexible tube into the heart to evaluate blood pressure and flow in the heart and surrounding arteries and veins.

Other diagnostic tests may include:

- Ultrasound exam of the heart (echocardiogram)

- Using magnets to create images of the heart (MRI)

- CT scan of the heart

Treatment

A small fistula that is not causing symptoms very often will not need treatment. Some small fistulas will close on their own. Often, even if they do not close, they will never cause symptoms or need treatment.

Infants with a larger fistula will need to have surgery to close the abnormal connection. The surgeon closes the site with a patch or stitches.

Another treatment option plugs up the opening without surgery, using a special wire (coil) that is inserted into the heart with a long, thin tube called a catheter. After the procedure in children, the fistula will most often close.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Children who have surgery mostly do well, although a small percentage may need to have surgery again. Most people with this condition have a normal lifespan.

Possible Complications

Complications include:

- Abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia)

- Heart attack

- Heart failure

- Opening (rupture) of the fistula

- Poor oxygen to the heart

Complications are more common in older people.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Coronary artery fistula is most often diagnosed during an exam by your provider. Contact your provider if your infant has symptoms of this condition.

Prevention

There is no known way to prevent this condition.

Alternative Names

Congenital heart defect - coronary artery fistula; Birth defect heart - coronary artery fistula

References

Bernstein D. General principles of treatment of congenital heart disease. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 483.

Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al. Acyanotic congenital heart disease: left-to-right shunt lesions. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2025:chap 475.

Valente AM, Dorfman AL, Babu-Narayan SV, Krieger EV. Congenital heart disease in the adolescent and adult. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 82.

Review Date 2/27/2024

Updated by: Thomas S. Metkus, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.